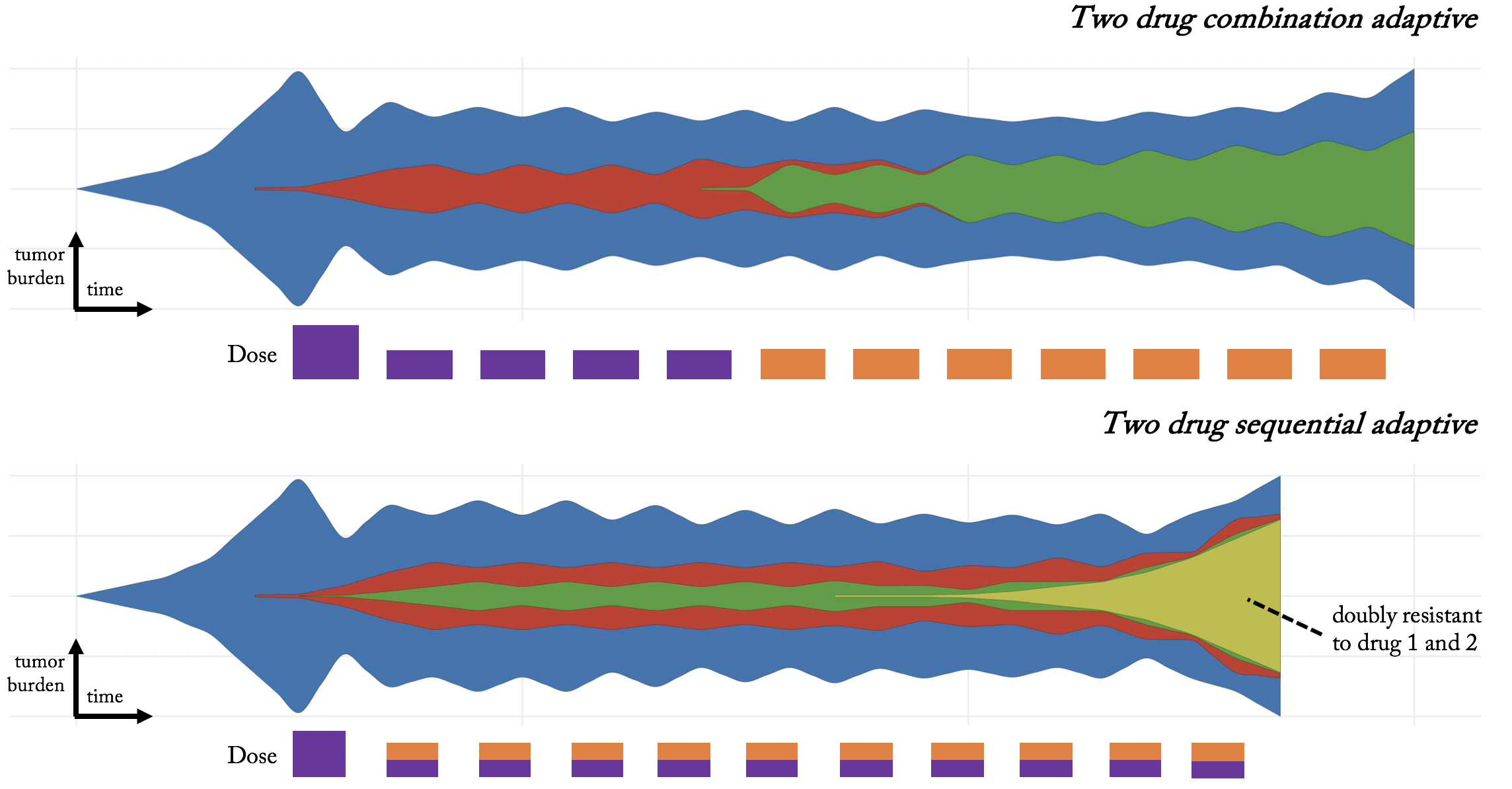

One of my driving interests during my time at Moffitt has been adaptive therapy. But more than that, I’m interested in extending these theories to administer multiple treatments adaptively. The complexity increases exponentially with each additional treatment considered. Take the schematic, below, which shows two possible multi-treatment adaptive therapy schedules.

Top panel: we might design an adaptive schedule for a single drug (purple), wait until drug 1 resistance almost emerges (five doses later), then administer the second drug (orange) adaptively. Bottom panel: alternatively, we might give a combination treatment adaptively, until a doubly-resistant subpopulation emerges.

Two paradigms for multi-treatment adaptive therapy

The differences between the approach are evident in the timing of each adaptive dose. In the first example, the timing between doses depends on the efficacy of a single drug. In the second, dose timing depends on total efficacy of combined purple and orange treatments, presumably faster than a single adaptive dose.

In this blog post, I review two paradigms to aid our pursuit of designing adaptive schedules with multiple treatments. The first, “primary-secondary” approach primarily relies on a single drug administered adaptively, but adds a secondary treatment with a slight delay after each adaptive dose. A second approach steers tumor evolution into “cycles,” returning the tumor back to its original pre-treatment state, regardless of tumor burden.

Primary – Secondary Evolutionary Adaptive Therapy

Single-treatment adaptive therapy has shown promise in delaying the onset of resistance, yet resistance may still eventually occur. The “Primary-Secondary” approach utilizes a well-timed secondary drug to mitigate against the inevitable emergence of resistance to primary treatment.

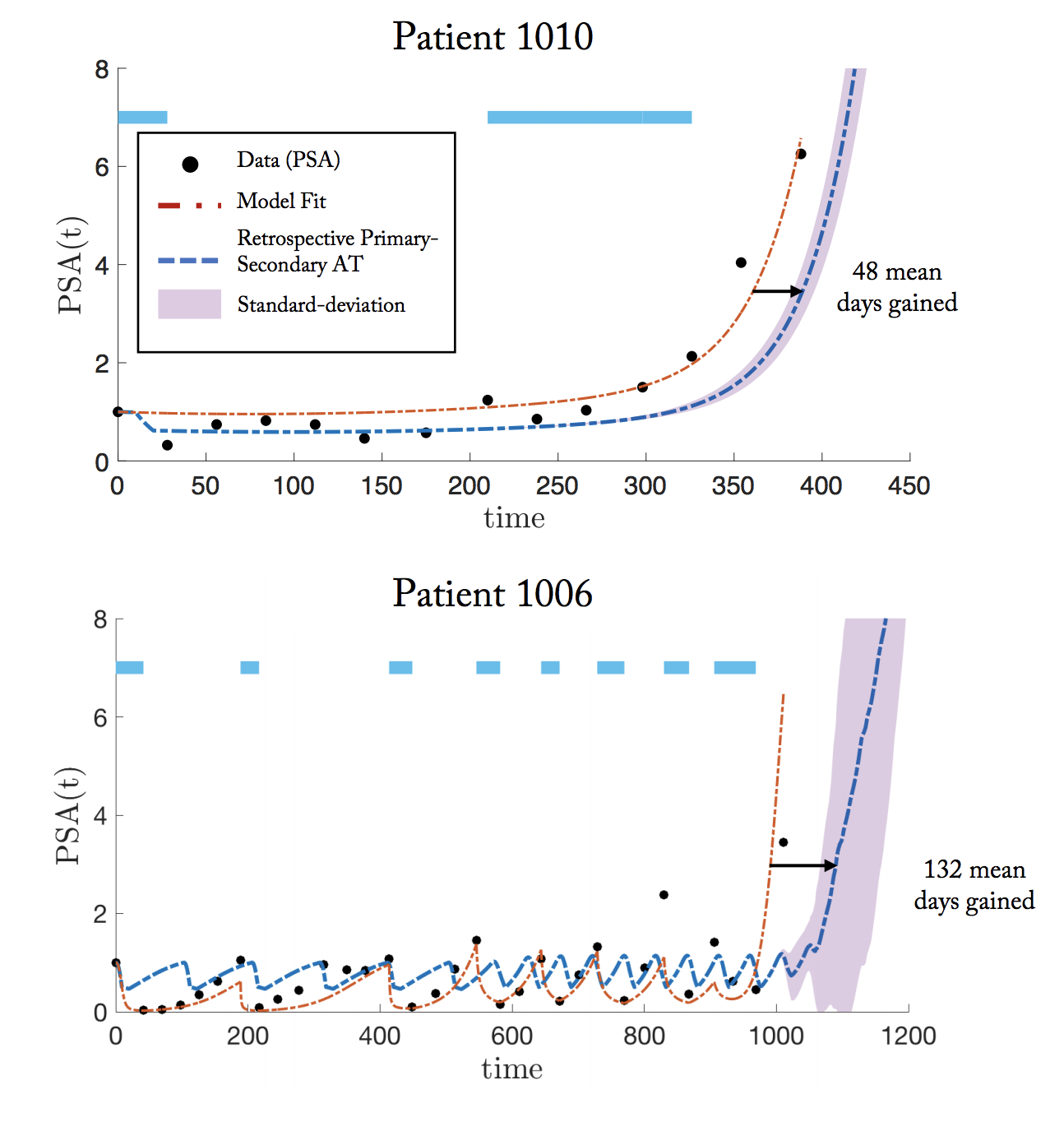

In the case of metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), the primary drug is Abiraterone, administered adaptively: on treatment until 50% reduction in burden biomarker (PSA), then off treatment until original burden levels. Below, we present two patients who have undergone this adaptive schedule, but PSA levels are no longer controlled after 2 doses (patient 1010) and 8 doses (patient 1006). Fitting a model to patient data and using identical initial conditions to seed the primary-secondary approach allows us to predict ‘days gained’ through the well-timed administration of docetaxel.

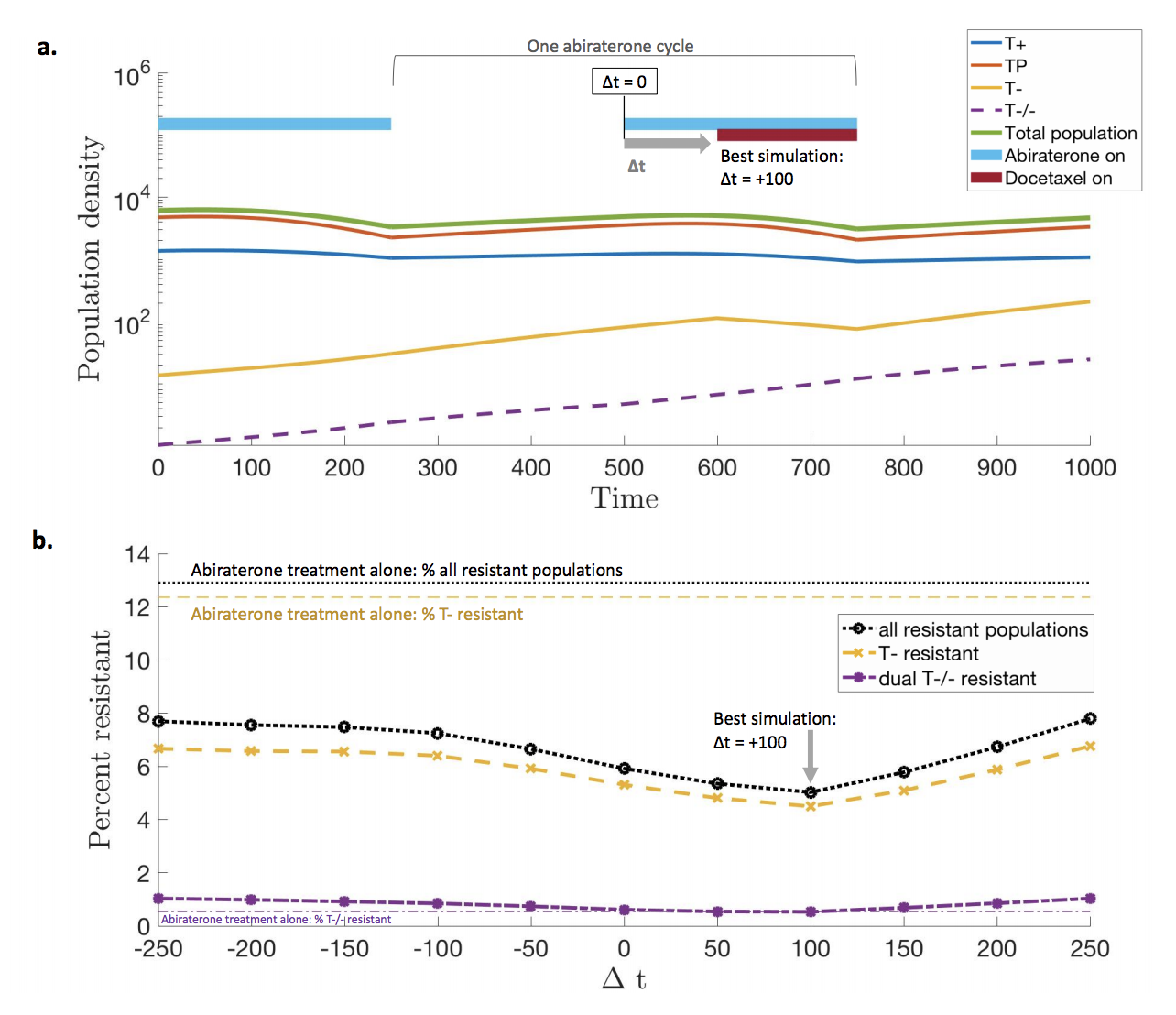

The purpose of this “secondary” docetaxel is to suppress resistant subpopulations that emerge little-by-little during each subsequent adaptive dose. Rather than indiscriminately determine the optimal timing of docetaxel throughout the entire course of treatment, we narrow our focus to the optimal timing within a single adaptive dose (off, then on abiraterone; see below).

An optimal treatment will target the fast proliferating resistant (yellow) subpopulation while not affecting cell types which are sensitive to the primary treatment. The lower panel shows the percent resistance after a single cycle. The optimal timing of secondary Docetaxel occurs just after the primary dose, after the primary Abiraterone targets sensitive (blue, red) cell types, and the resistant (yellow) is maximally proliferating.

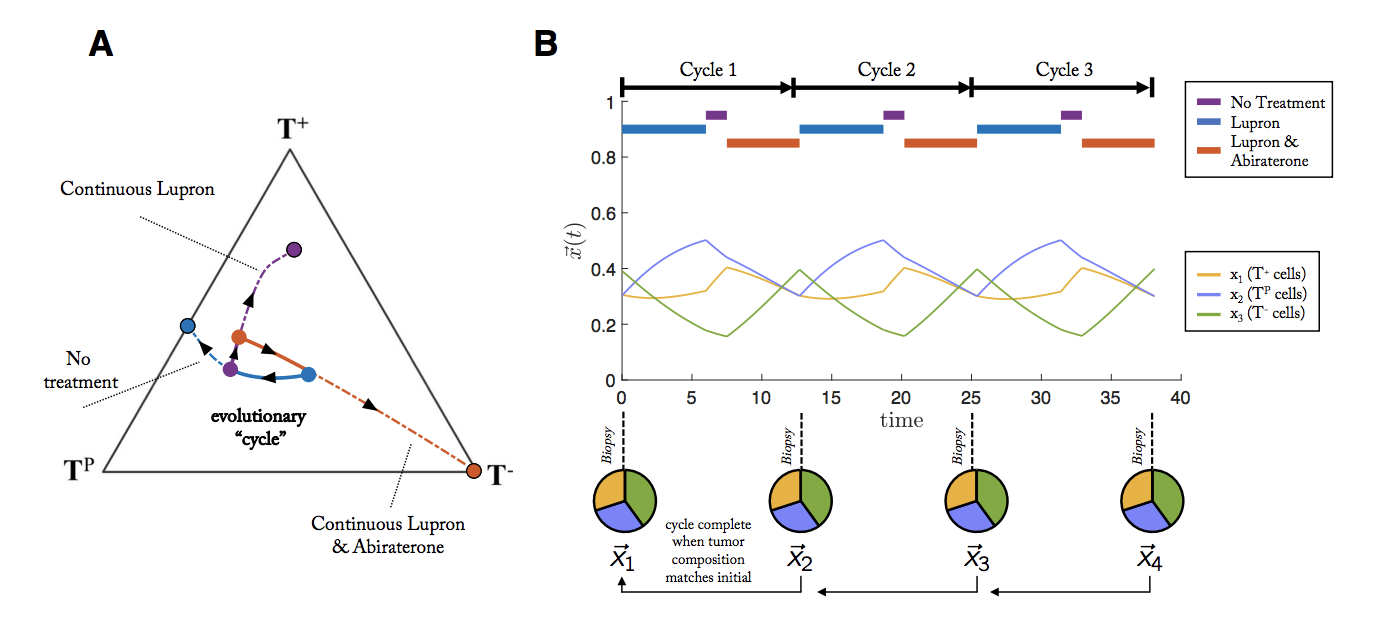

Evolutionary cycles

Another strategy for multi-drug adaptive therapies is called evolutionary cycles, first introduced by Paul Newton, here and extended to prostate cancer in our preprint here.

A cycle is defined as a treatment regimen that steers the tumor into periodic and repeatable temporal dynamics of tumor composition. As seen in the figure above, a weekly biopsy shows the frequencies (pie charts) of 4 phenotypes (blue, green, red, yellow) in the evolving tumor over time. At each time step, the state of the tumor is given by a vector, x, indicating the frequency of each cell type composing the tumor. In this example, the fifth week produces a tumor composition, x, which is approximately equivalent to the tumor composition at the start of therapy (x5 ≈ x1). Theoretically, such cycles could be repeated ad infinitum to steer and trap tumor evolution in a repeatable (and controllable) cycle.

Adapting to tumor adaptations

I think a huge key moving forward will be remembering that each treatment administered inevitably has an evolutionary fallback (resistance), but each resistance mechanism carries along constraints. As the tumor adapts to treatment, so also do its constraints and advantages ebb and flow.

“At a minimum, in explaining evolutionary pathways through time, the constraints imposed by history rise to equal prominence with the immediate advantages of adaptation."

- Stephen J Gould –

We likely have many unexplored paradigms for the evolutionary treatment of tumors. For example, others have proposed evolutionary double-binds or a first-strike-second-strike paradigm. Historically, the problem of drug resistance has often enlisted the help of mathematical modeling in designing optimal therapy schedules, and I see no sign of that trend diminishing.

I Contain Multitudes

Ed Yong

"In I Contain Multitudes, Yong synthesizes literally hundreds and hundreds of papers, but he never overwhelms you with the science. He just keeps imparting one surprising, fascinating insight after the next."