A version of this article originally appeared on Ryan O. Schenck's blog, here.

For those who are interested in agent-based models of cancer, this has been one of the most exciting months of mathematical oncology in recent memory. The purpose of this blog is to summarize the findings of several cancer (and one non-cancer) models. We will attempt to showcase the harmony between these preprints and go on to detail what is still unknown.

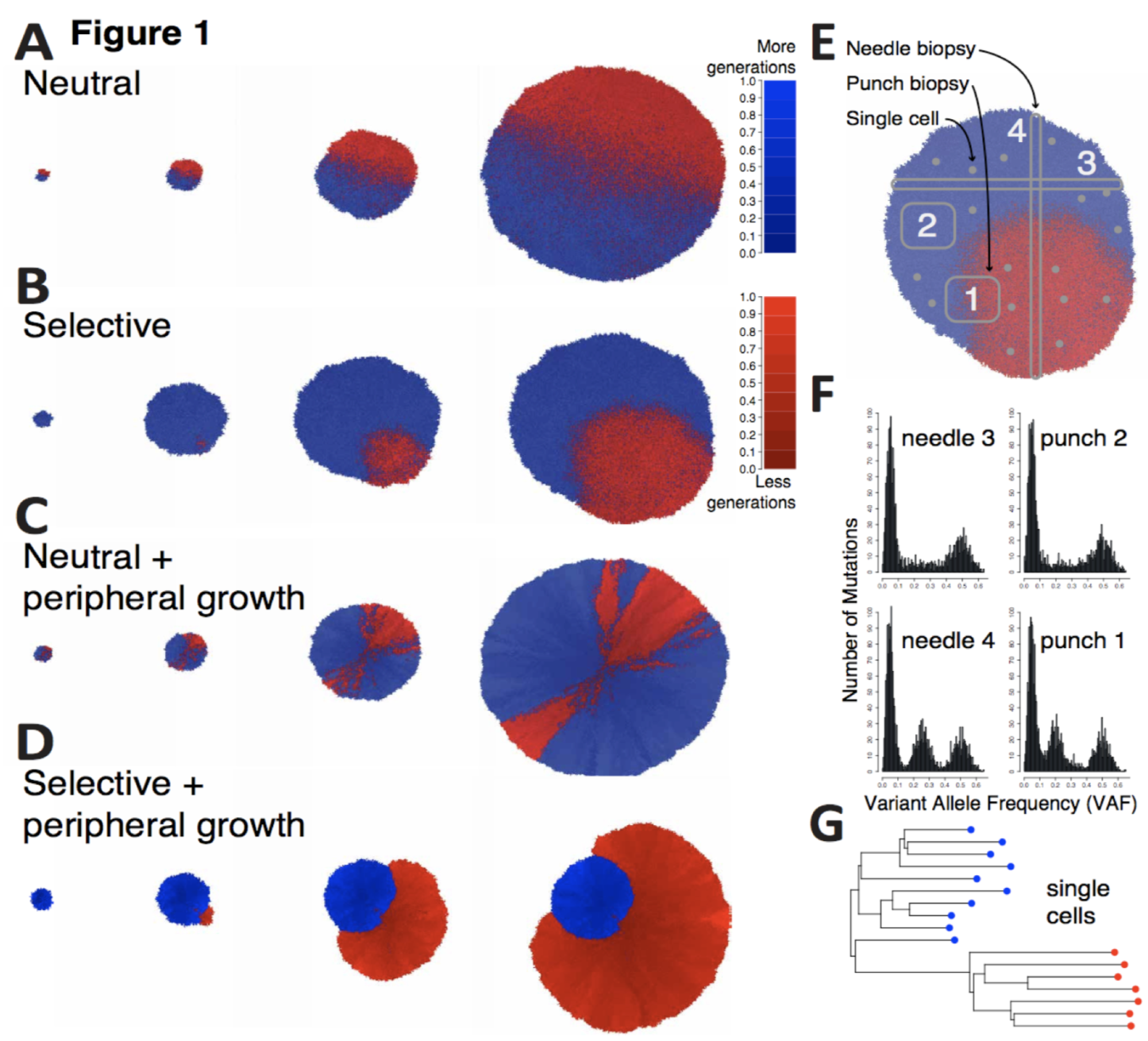

First up, a preprint by Kate Chkhaidze called “Spatially constrained tumour growth affects the patterns of clonal selection and neutral drift in cancer genomic data.” (see figure below).

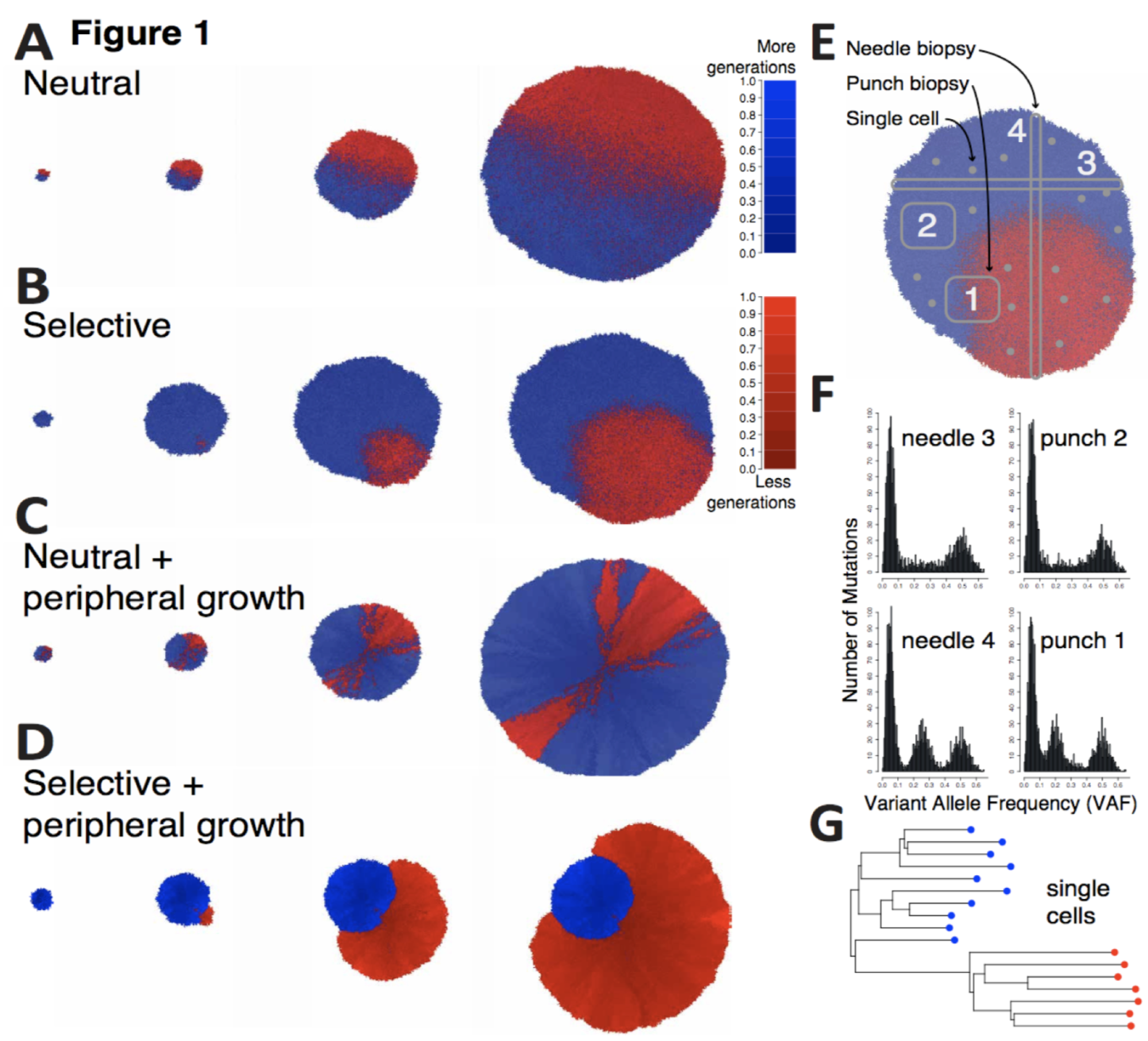

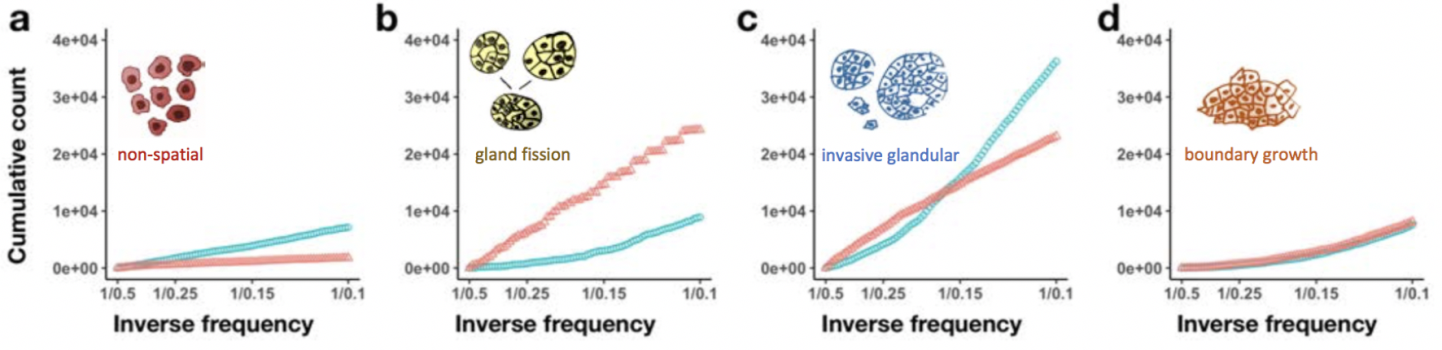

In this paper, Chkhaidze introduces two types of spatially-explicit tumor growth models: boundary-driven (only cells on the edge can proliferate) and homogeneous (all cells can divide). Each model is subjected to sequencing (needle, punch, single cell type biopsies) for both neutral and selective subclonal mutations.

The paper focuses on the sampling bias question: the neutral, boundary-driven case leads to interesting spatial patterns (genetic draft or gene surfing, figure 1C above), and therefore has a high likelihood of sampling bias. Alternatively, certain patterns of growth are easiest to recover, especially when spatial constraints are limited and the number of unknown parameters are lowest. Depending on the spatial growth assumptions (homogeneous vs boundary-driven), measurement bias can artificially increase the apparent selection (depending on sampling type). In other words, some tumors may artificially measure higher on metrics of subclonal selection.

This sampling bias has important implications and requires further examination of mutations within their spatial contexts. When we think about this paper in various tissue types we can see how space makes a massive difference! Our group has recently released two preprints that show effective subclonal selection differences without alterations in cell-specific fitness or mutation rate. The first is in non-cancerous tissue, and the second in premalignant ductal carcinomas.

In this paper, Chkhaidze introduces two types of spatially-explicit tumor growth models: boundary-driven (only cells on the edge can proliferate) and homogeneous (all cells can divide). Each model is subjected to sequencing (needle, punch, single cell type biopsies) for both neutral and selective subclonal mutations.

The paper focuses on the sampling bias question: the neutral, boundary-driven case leads to interesting spatial patterns (genetic draft or gene surfing, figure 1C above), and therefore has a high likelihood of sampling bias. Alternatively, certain patterns of growth are easiest to recover, especially when spatial constraints are limited and the number of unknown parameters are lowest. Depending on the spatial growth assumptions (homogeneous vs boundary-driven), measurement bias can artificially increase the apparent selection (depending on sampling type). In other words, some tumors may artificially measure higher on metrics of subclonal selection.

This sampling bias has important implications and requires further examination of mutations within their spatial contexts. When we think about this paper in various tissue types we can see how space makes a massive difference! Our group has recently released two preprints that show effective subclonal selection differences without alterations in cell-specific fitness or mutation rate. The first is in non-cancerous tissue, and the second in premalignant ductal carcinomas.

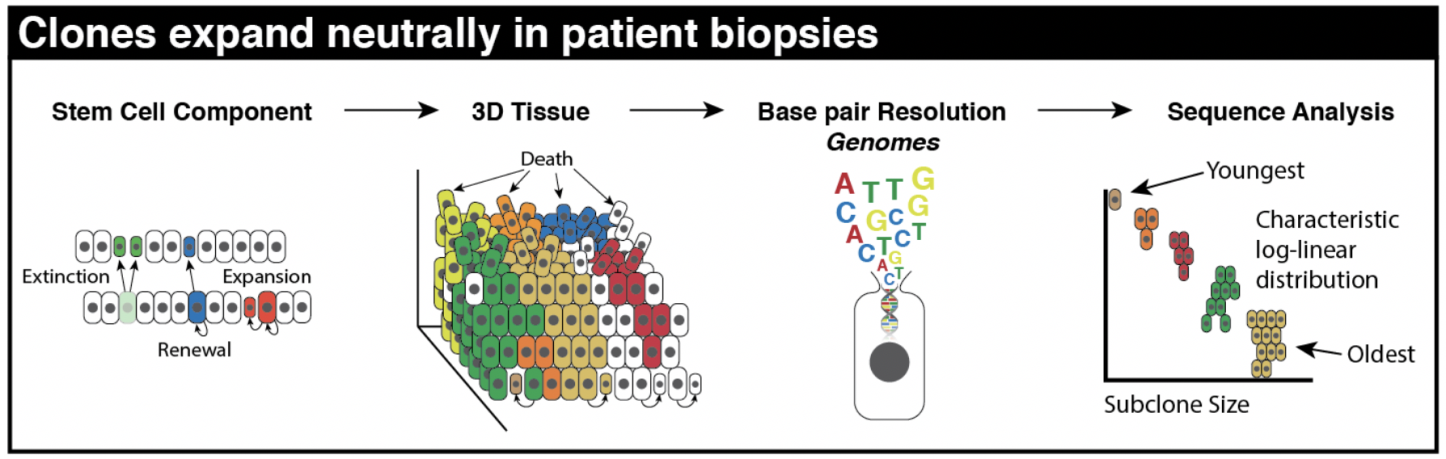

Oncogenic drivers may still exist in normal tissue, even existing in large numbers! We show that the largest of these subclones must be the oldest subclones. Importantly, mutations in normal skin do not disrupt homeostatic mechanisms, leaving intact the natural architecture and tissue turnover processes.

How did we elucidate the importance of homeostasis as a mechanism for sustained neutrality? While subclones may expand over a lifetime, it is not cell-specific selection in the ‘traditional’ sense. It’s expansion due to persistence, not proliferation. This means simply surviving longer in the right spot at the right time. But again, why this emergent behavior?

The key here is that selection for quickly proliferating clones will lead to the collapse of the tissue. Our 3-dimensional agent-based model constructed to represent the tissue architecture of a homeostatic epidermis recapitulates important homeostatic behaviors. Certain modes of evolution simply are not tolerated within this homeostatic tissue architecture, without additionally facilitating the complete destruction of tissue. In this way, any clonal expansion is limited by the fitness advantage it has over its neighbors.

Oncogenic drivers may still exist in normal tissue, even existing in large numbers! We show that the largest of these subclones must be the oldest subclones. Importantly, mutations in normal skin do not disrupt homeostatic mechanisms, leaving intact the natural architecture and tissue turnover processes.

How did we elucidate the importance of homeostasis as a mechanism for sustained neutrality? While subclones may expand over a lifetime, it is not cell-specific selection in the ‘traditional’ sense. It’s expansion due to persistence, not proliferation. This means simply surviving longer in the right spot at the right time. But again, why this emergent behavior?

The key here is that selection for quickly proliferating clones will lead to the collapse of the tissue. Our 3-dimensional agent-based model constructed to represent the tissue architecture of a homeostatic epidermis recapitulates important homeostatic behaviors. Certain modes of evolution simply are not tolerated within this homeostatic tissue architecture, without additionally facilitating the complete destruction of tissue. In this way, any clonal expansion is limited by the fitness advantage it has over its neighbors.

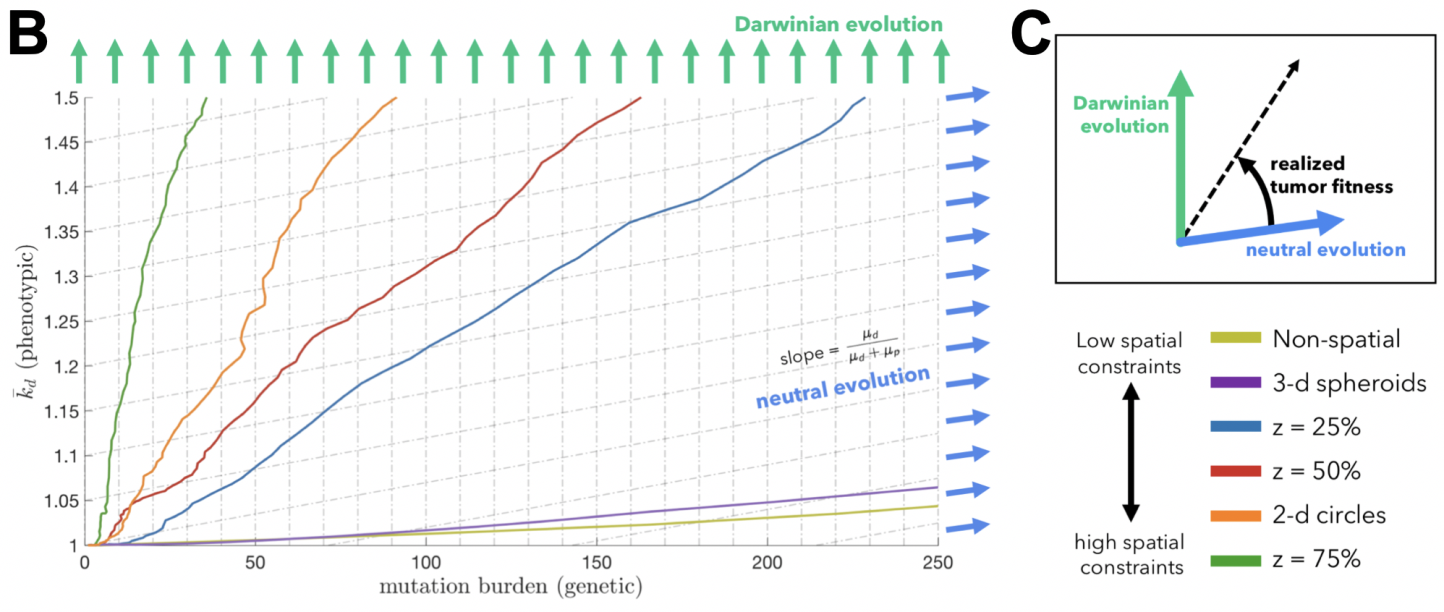

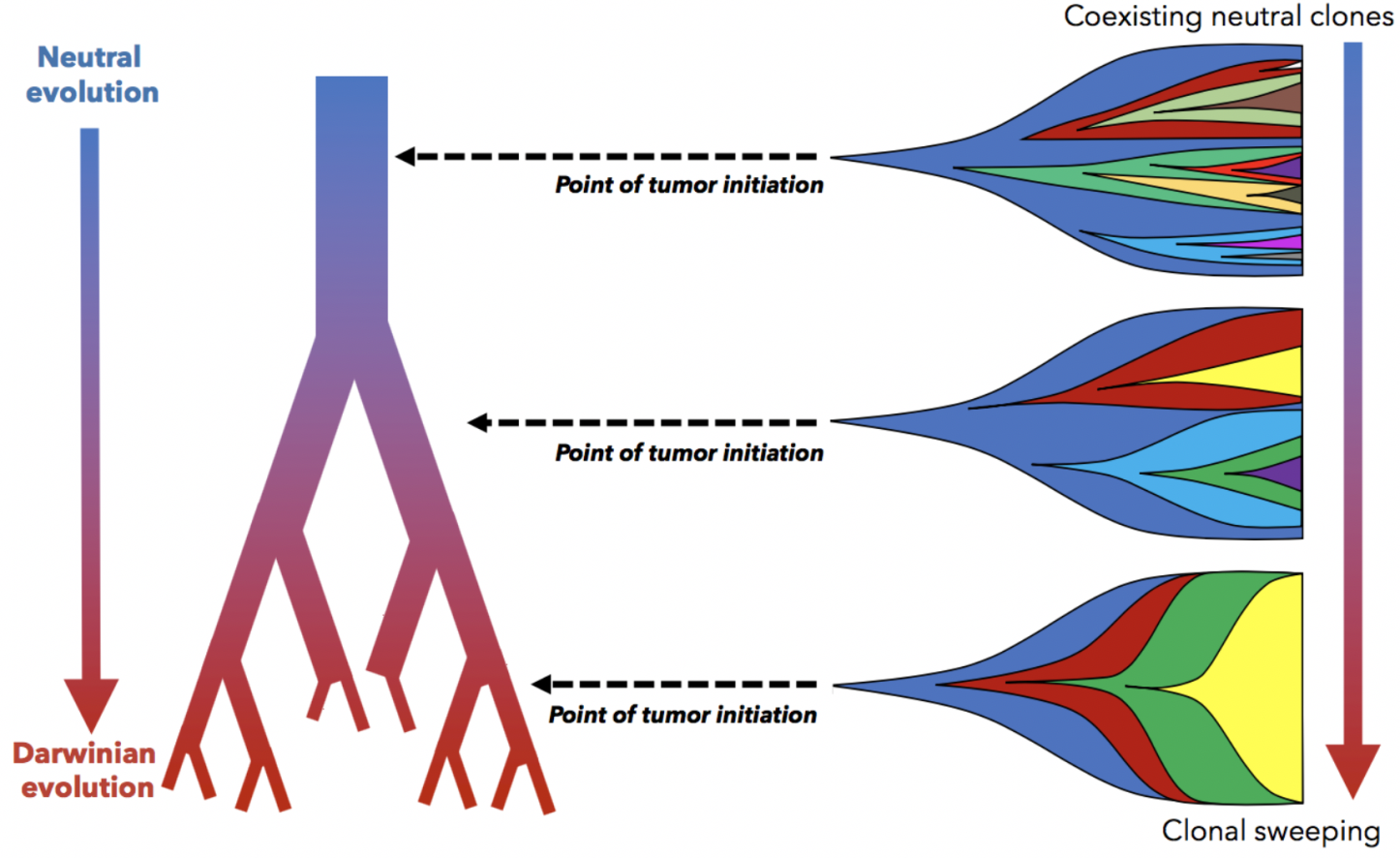

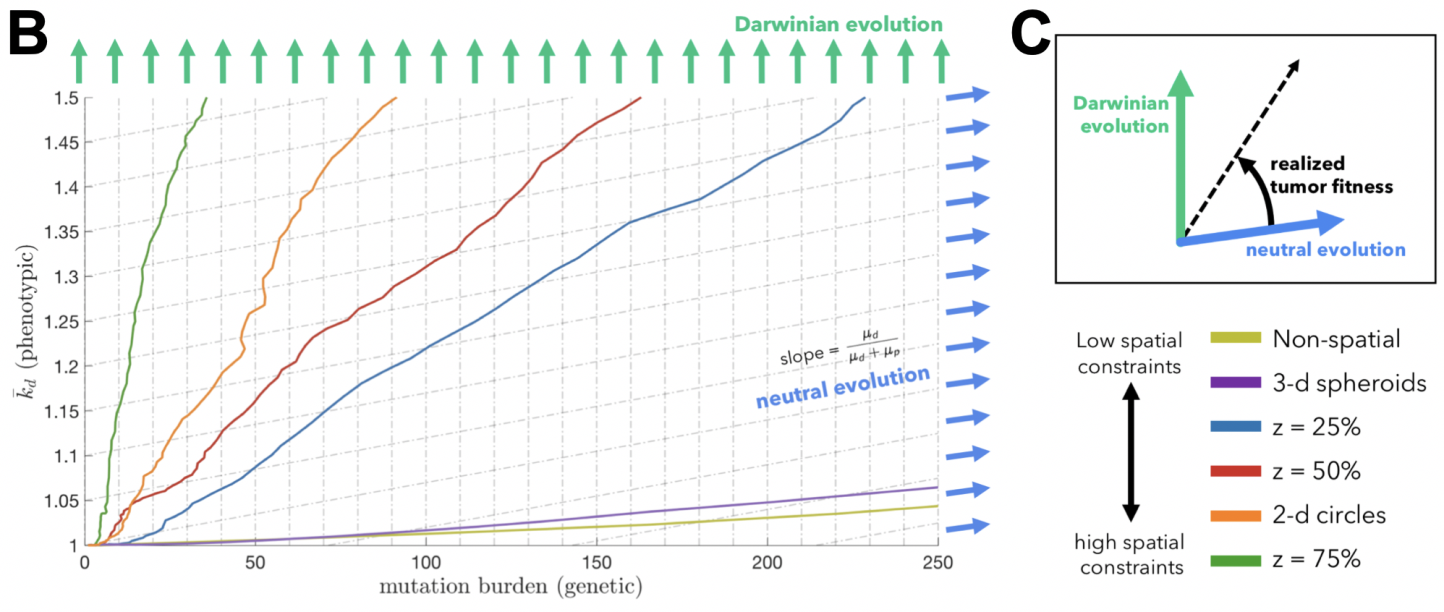

In a fun experiment, we simulated identical cell-specific parameters in a few additional settings: 3-dimensional spheroids, 2-dimensional circles, and non-spatial models. Below, we show tumor evolution on a neutral (x-axis) and Darwinian (y-axis) plane. Tumor evolutionary trajectories for 3-dimensional spheroids are more neutral (left-to-right) – and almost overlapping with non-spatial models! It’s initially quite jarring, but it makes some sense, as cells on a 2-dimensional lattice have less free-space to divide than their 3-dimensional counterparts.

In a fun experiment, we simulated identical cell-specific parameters in a few additional settings: 3-dimensional spheroids, 2-dimensional circles, and non-spatial models. Below, we show tumor evolution on a neutral (x-axis) and Darwinian (y-axis) plane. Tumor evolutionary trajectories for 3-dimensional spheroids are more neutral (left-to-right) – and almost overlapping with non-spatial models! It’s initially quite jarring, but it makes some sense, as cells on a 2-dimensional lattice have less free-space to divide than their 3-dimensional counterparts.

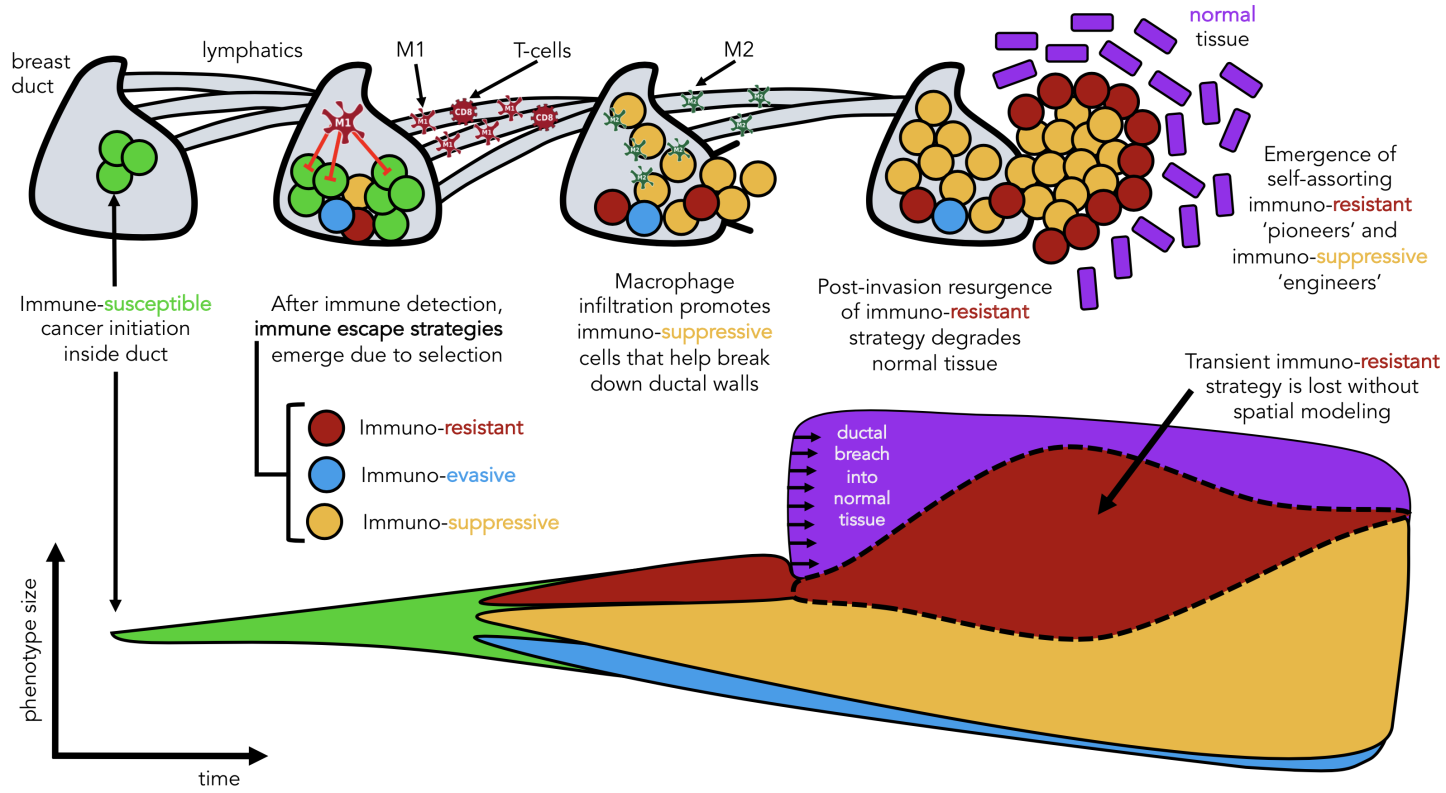

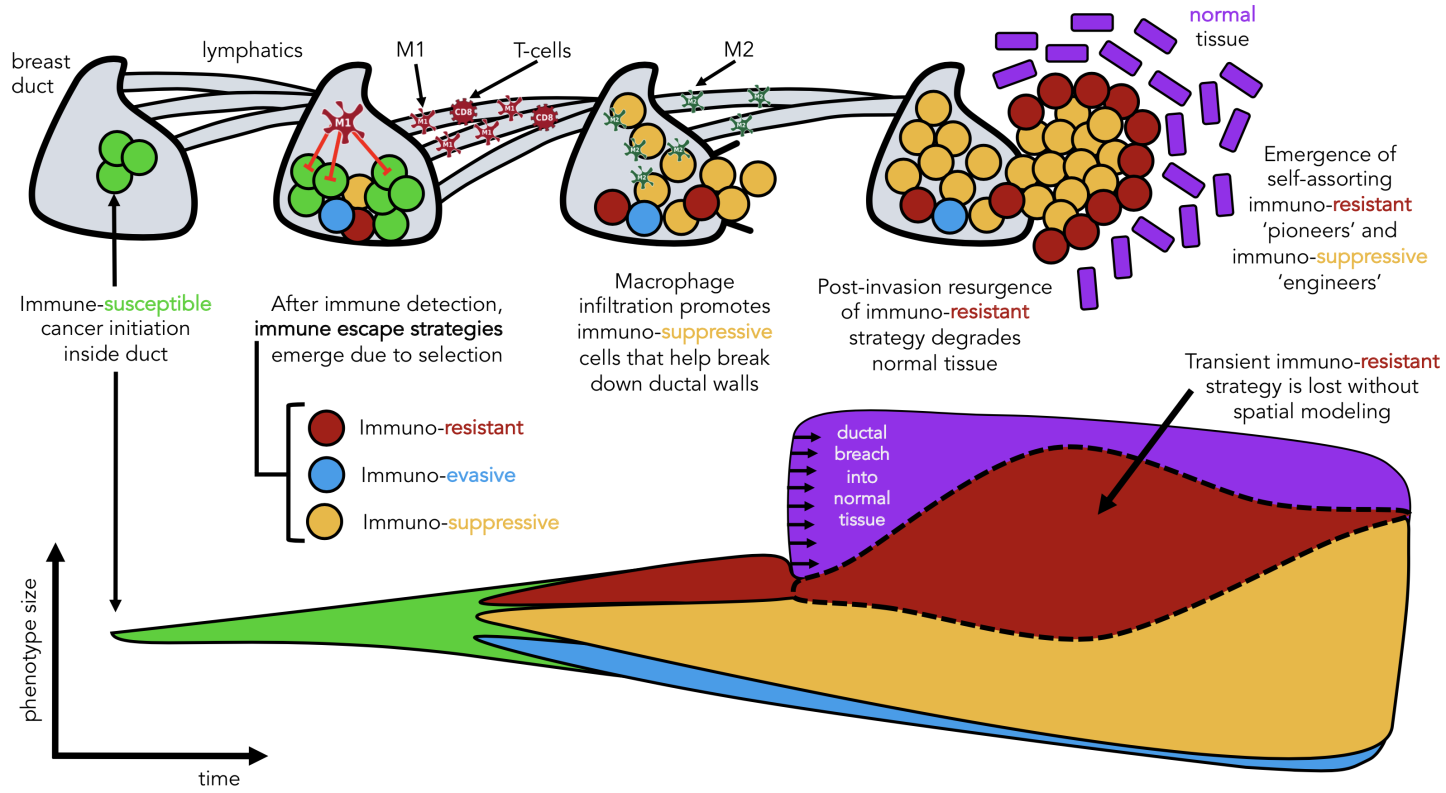

Seeded from immunohistochemistry imaging data of ductal carinomas (see above), the model tracks the evolution of various immune escape strategies which we classify into three broad categories: immunoevasion (blue), immunoresistance (red), and immunosuppression (yellow), all invading into normal stroma (purple).

We learned two things: macrophages are an important ‘public good’ in facilitating invasion, but lose importance after invasion when dynamics are mainly driven by stromal interactions. Second, we learned of a self-assorting engineer-pioneer dynamic of two immunoediting strategies (suppressive and resistant). The first of these conclusions may have been elucidated by the non-spatial modeling, but the second is entirely lost without spatially explicit modeling frameworks!

Seeded from immunohistochemistry imaging data of ductal carinomas (see above), the model tracks the evolution of various immune escape strategies which we classify into three broad categories: immunoevasion (blue), immunoresistance (red), and immunosuppression (yellow), all invading into normal stroma (purple).

We learned two things: macrophages are an important ‘public good’ in facilitating invasion, but lose importance after invasion when dynamics are mainly driven by stromal interactions. Second, we learned of a self-assorting engineer-pioneer dynamic of two immunoediting strategies (suppressive and resistant). The first of these conclusions may have been elucidated by the non-spatial modeling, but the second is entirely lost without spatially explicit modeling frameworks!

Here, we might try to sum up what we have learned: the choice of model should be heavily influenced by the mode of evolution of the biological system of study. We also need unified metrics. The best metrics are ones that can easily compare model outputs directly to data. On the other hand, this is where modeling can shine: showing that data can be recapitulated by several models or parameter combinations.

This is where the heart of the neutral debate lies: isn’t the simplest explanation the most likely? Perhaps we are biased, but we believe that this discussion on neutrality may not have been initiated without the aid of mathematical modeling and will continue to prove to be a critical component to continue answering questions where data resolution is not there or not yet possible to obtain.

Here, we might try to sum up what we have learned: the choice of model should be heavily influenced by the mode of evolution of the biological system of study. We also need unified metrics. The best metrics are ones that can easily compare model outputs directly to data. On the other hand, this is where modeling can shine: showing that data can be recapitulated by several models or parameter combinations.

This is where the heart of the neutral debate lies: isn’t the simplest explanation the most likely? Perhaps we are biased, but we believe that this discussion on neutrality may not have been initiated without the aid of mathematical modeling and will continue to prove to be a critical component to continue answering questions where data resolution is not there or not yet possible to obtain.

In this paper, Chkhaidze introduces two types of spatially-explicit tumor growth models: boundary-driven (only cells on the edge can proliferate) and homogeneous (all cells can divide). Each model is subjected to sequencing (needle, punch, single cell type biopsies) for both neutral and selective subclonal mutations.

The paper focuses on the sampling bias question: the neutral, boundary-driven case leads to interesting spatial patterns (genetic draft or gene surfing, figure 1C above), and therefore has a high likelihood of sampling bias. Alternatively, certain patterns of growth are easiest to recover, especially when spatial constraints are limited and the number of unknown parameters are lowest. Depending on the spatial growth assumptions (homogeneous vs boundary-driven), measurement bias can artificially increase the apparent selection (depending on sampling type). In other words, some tumors may artificially measure higher on metrics of subclonal selection.

This sampling bias has important implications and requires further examination of mutations within their spatial contexts. When we think about this paper in various tissue types we can see how space makes a massive difference! Our group has recently released two preprints that show effective subclonal selection differences without alterations in cell-specific fitness or mutation rate. The first is in non-cancerous tissue, and the second in premalignant ductal carcinomas.

In this paper, Chkhaidze introduces two types of spatially-explicit tumor growth models: boundary-driven (only cells on the edge can proliferate) and homogeneous (all cells can divide). Each model is subjected to sequencing (needle, punch, single cell type biopsies) for both neutral and selective subclonal mutations.

The paper focuses on the sampling bias question: the neutral, boundary-driven case leads to interesting spatial patterns (genetic draft or gene surfing, figure 1C above), and therefore has a high likelihood of sampling bias. Alternatively, certain patterns of growth are easiest to recover, especially when spatial constraints are limited and the number of unknown parameters are lowest. Depending on the spatial growth assumptions (homogeneous vs boundary-driven), measurement bias can artificially increase the apparent selection (depending on sampling type). In other words, some tumors may artificially measure higher on metrics of subclonal selection.

This sampling bias has important implications and requires further examination of mutations within their spatial contexts. When we think about this paper in various tissue types we can see how space makes a massive difference! Our group has recently released two preprints that show effective subclonal selection differences without alterations in cell-specific fitness or mutation rate. The first is in non-cancerous tissue, and the second in premalignant ductal carcinomas.

Homeostasis constrains evolution

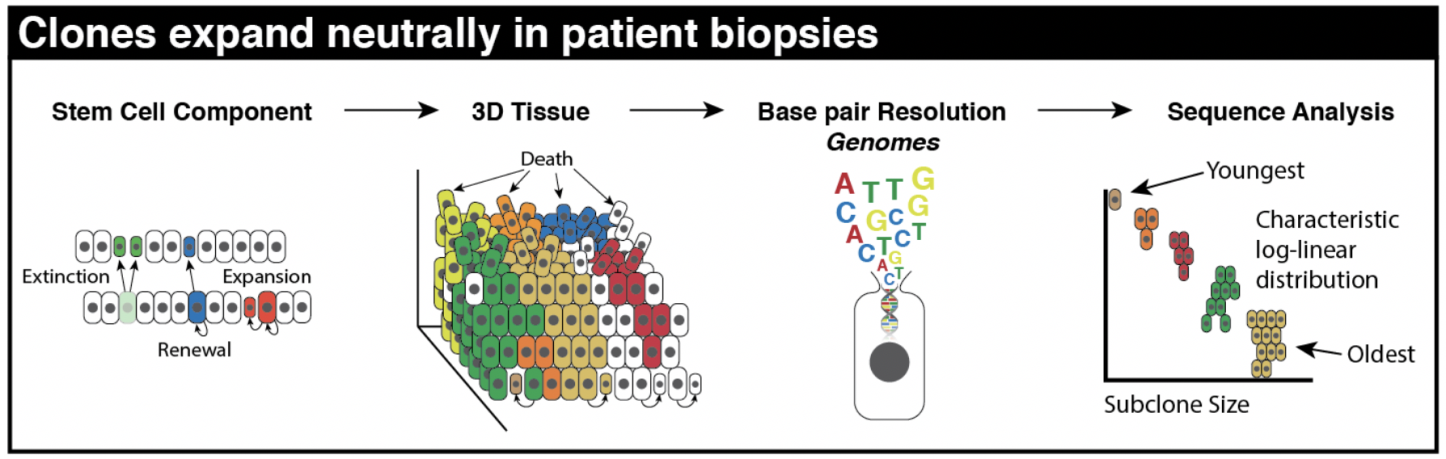

In the first preprint, “Clonal Architecture of the Epidermis: Homeostasis Limits Keratinocyte Evolution,” we show that homeostasis inherent to normal epithelia naturally imposes neutral log-linear subclone size distributions (see schematic below). Oncogenic drivers may still exist in normal tissue, even existing in large numbers! We show that the largest of these subclones must be the oldest subclones. Importantly, mutations in normal skin do not disrupt homeostatic mechanisms, leaving intact the natural architecture and tissue turnover processes.

How did we elucidate the importance of homeostasis as a mechanism for sustained neutrality? While subclones may expand over a lifetime, it is not cell-specific selection in the ‘traditional’ sense. It’s expansion due to persistence, not proliferation. This means simply surviving longer in the right spot at the right time. But again, why this emergent behavior?

The key here is that selection for quickly proliferating clones will lead to the collapse of the tissue. Our 3-dimensional agent-based model constructed to represent the tissue architecture of a homeostatic epidermis recapitulates important homeostatic behaviors. Certain modes of evolution simply are not tolerated within this homeostatic tissue architecture, without additionally facilitating the complete destruction of tissue. In this way, any clonal expansion is limited by the fitness advantage it has over its neighbors.

Oncogenic drivers may still exist in normal tissue, even existing in large numbers! We show that the largest of these subclones must be the oldest subclones. Importantly, mutations in normal skin do not disrupt homeostatic mechanisms, leaving intact the natural architecture and tissue turnover processes.

How did we elucidate the importance of homeostasis as a mechanism for sustained neutrality? While subclones may expand over a lifetime, it is not cell-specific selection in the ‘traditional’ sense. It’s expansion due to persistence, not proliferation. This means simply surviving longer in the right spot at the right time. But again, why this emergent behavior?

The key here is that selection for quickly proliferating clones will lead to the collapse of the tissue. Our 3-dimensional agent-based model constructed to represent the tissue architecture of a homeostatic epidermis recapitulates important homeostatic behaviors. Certain modes of evolution simply are not tolerated within this homeostatic tissue architecture, without additionally facilitating the complete destruction of tissue. In this way, any clonal expansion is limited by the fitness advantage it has over its neighbors.

Tissue architecture & effective selection

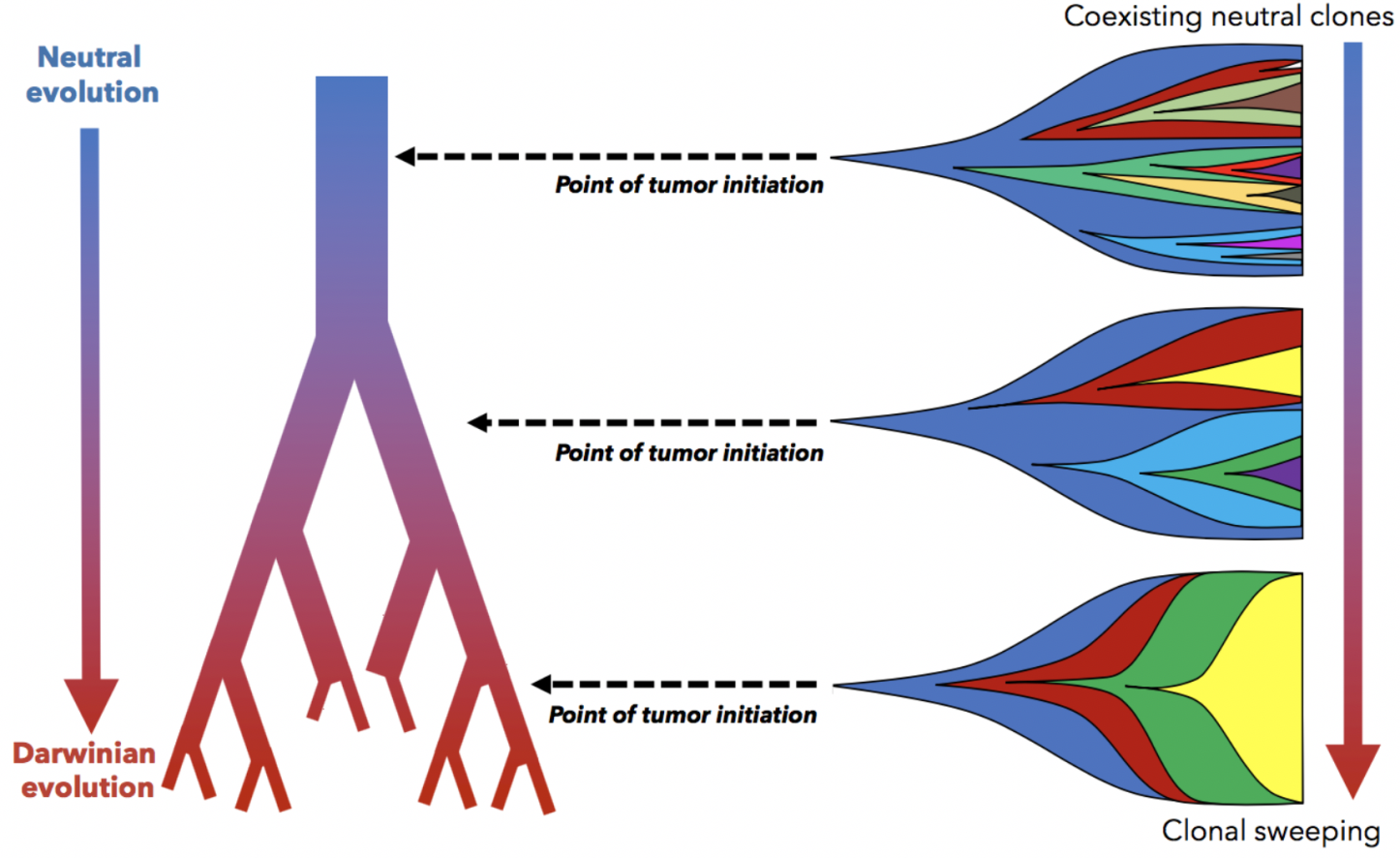

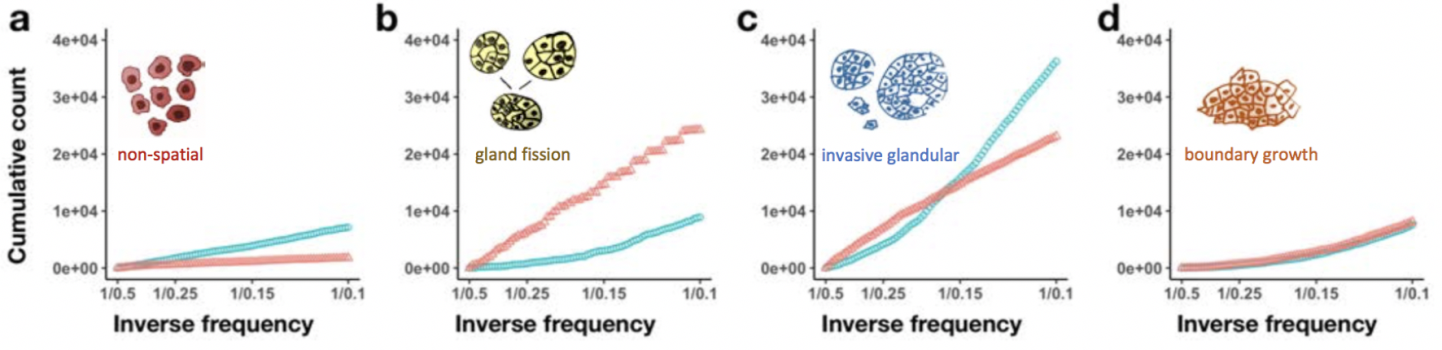

It’s clear that spatial constraints can no longer be ignored in the discussion of tissue evolution, normal or cancerous. More nuance is required when interpreting our model results. A second preprint from our group, titled “Tissue structure accelerates evolution: premalignant sweeps precede neutral expansion,” quantifies how spatial constraints alter the evolutionary trajectory of a single tumor. One case where spatial constraints play a role is pre-malignant ductal carcinoma growth. These growths may initiate at various points within the ductal network (and thus, various degrees of spatial constraints). Tumors initiated in smaller, tightly constrained ducts impose a strong negative selection on weaker subclones, enabling faster sweeping of new, fitter clones (i.e. Darwinian evolution). Conversely, tumors initiated in larger, less constrained ducts are driven by neutral evolutionary mode, all without changes in cell-specific fitness. In a fun experiment, we simulated identical cell-specific parameters in a few additional settings: 3-dimensional spheroids, 2-dimensional circles, and non-spatial models. Below, we show tumor evolution on a neutral (x-axis) and Darwinian (y-axis) plane. Tumor evolutionary trajectories for 3-dimensional spheroids are more neutral (left-to-right) – and almost overlapping with non-spatial models! It’s initially quite jarring, but it makes some sense, as cells on a 2-dimensional lattice have less free-space to divide than their 3-dimensional counterparts.

In a fun experiment, we simulated identical cell-specific parameters in a few additional settings: 3-dimensional spheroids, 2-dimensional circles, and non-spatial models. Below, we show tumor evolution on a neutral (x-axis) and Darwinian (y-axis) plane. Tumor evolutionary trajectories for 3-dimensional spheroids are more neutral (left-to-right) – and almost overlapping with non-spatial models! It’s initially quite jarring, but it makes some sense, as cells on a 2-dimensional lattice have less free-space to divide than their 3-dimensional counterparts.

Seeding spatial models

In each of these cases, the important result may have been lost without spatially-explicit models. In a non-spatial setting, fitter clones may rarely be constrained from expanding, with significant genetic hitch-hikers. Contrasting that to a spatial setting where many fitter clones may indeed exist – but are unable to sweep. In some cases, space may actually help the sweeping by enabling a Goldilocks zone of cellular mixing and negative selection allowing expansion and sweeping to occur simultaneously. We’ve also taken steps to show that important transient behavior may be lost without considering space. In another preprint, “Macrophage-mediated immunoediting drives ductal carcinoma evolution: Space is the game changer,” we have explicitly compared differences between non-spatial game theoretic models with spatially-explicit formulations. Seeded from immunohistochemistry imaging data of ductal carinomas (see above), the model tracks the evolution of various immune escape strategies which we classify into three broad categories: immunoevasion (blue), immunoresistance (red), and immunosuppression (yellow), all invading into normal stroma (purple).

We learned two things: macrophages are an important ‘public good’ in facilitating invasion, but lose importance after invasion when dynamics are mainly driven by stromal interactions. Second, we learned of a self-assorting engineer-pioneer dynamic of two immunoediting strategies (suppressive and resistant). The first of these conclusions may have been elucidated by the non-spatial modeling, but the second is entirely lost without spatially explicit modeling frameworks!

Seeded from immunohistochemistry imaging data of ductal carinomas (see above), the model tracks the evolution of various immune escape strategies which we classify into three broad categories: immunoevasion (blue), immunoresistance (red), and immunosuppression (yellow), all invading into normal stroma (purple).

We learned two things: macrophages are an important ‘public good’ in facilitating invasion, but lose importance after invasion when dynamics are mainly driven by stromal interactions. Second, we learned of a self-assorting engineer-pioneer dynamic of two immunoediting strategies (suppressive and resistant). The first of these conclusions may have been elucidated by the non-spatial modeling, but the second is entirely lost without spatially explicit modeling frameworks!

Space is really important

If you’re keeping track, we have attributed responsibility to the spatial tissue architecture for four phenomena:- introducing measurement bias in 2-dimensional tissues

- limiting fitness/selection in 3-dimensional homeostatic tissue

- increasing effective subclonal selection in 3-dimensional ductal carcinomas

- facilitating self-assortment of cooperating phenotypes

Here, we might try to sum up what we have learned: the choice of model should be heavily influenced by the mode of evolution of the biological system of study. We also need unified metrics. The best metrics are ones that can easily compare model outputs directly to data. On the other hand, this is where modeling can shine: showing that data can be recapitulated by several models or parameter combinations.

This is where the heart of the neutral debate lies: isn’t the simplest explanation the most likely? Perhaps we are biased, but we believe that this discussion on neutrality may not have been initiated without the aid of mathematical modeling and will continue to prove to be a critical component to continue answering questions where data resolution is not there or not yet possible to obtain.

Here, we might try to sum up what we have learned: the choice of model should be heavily influenced by the mode of evolution of the biological system of study. We also need unified metrics. The best metrics are ones that can easily compare model outputs directly to data. On the other hand, this is where modeling can shine: showing that data can be recapitulated by several models or parameter combinations.

This is where the heart of the neutral debate lies: isn’t the simplest explanation the most likely? Perhaps we are biased, but we believe that this discussion on neutrality may not have been initiated without the aid of mathematical modeling and will continue to prove to be a critical component to continue answering questions where data resolution is not there or not yet possible to obtain.

Advertisement

Adaptive Oncogenesis

James DeGregori

Popular understanding holds that genetic changes create cancer. James DeGregori uses evolutionary principles to propose a new way of thinking about cancer’s occurrence. Cancer is as much a disease of evolution as it is of mutation, one in which mutated cells outcompete healthy cells in the ecosystem of the body’s tissues.

Consider buying the book to help support site maintenance expenses. I've read and personally recommend each.

References:

- Spatially constrained tumour growth affects the patterns of clonal selection and neutral drift in cancer genomic data. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/544536v2

- Tissue structure accelerates evolution: premalignant sweeps precede neutral expansion. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/542019v1

- Clonal Architecture of the Epidermis: Homeostasis Limits Keratinocyte Evolution. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/548131v1

- Spatial structure governs the mode of tumour evolution. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/586735v1

- Macrophage-mediated immunoediting drives ductal carcinoma evolution: Space is the game changer. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/594598v1