A version of this article originally appeared on The Mathematical Oncology blog,

here.

Math Oncology 101

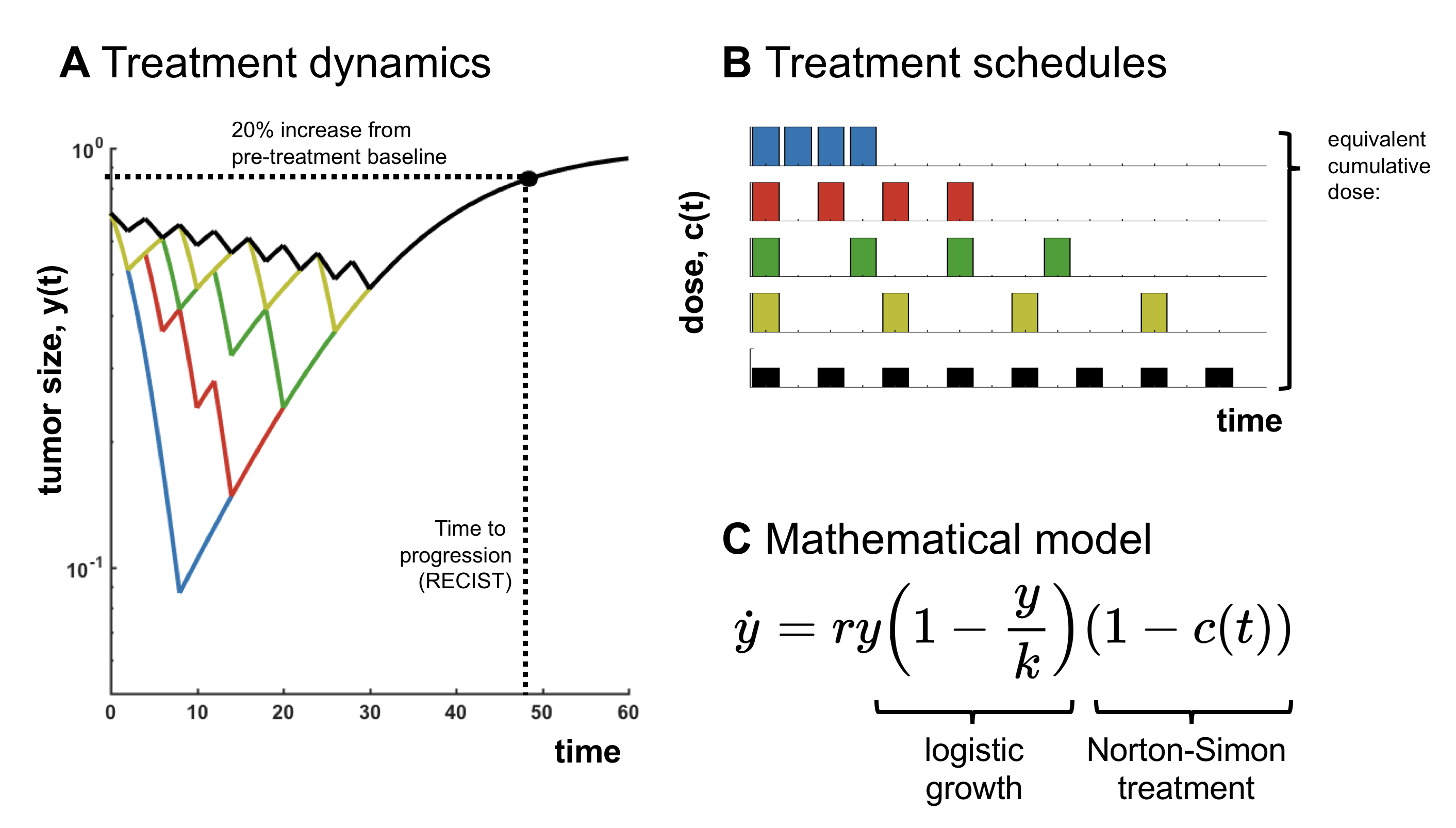

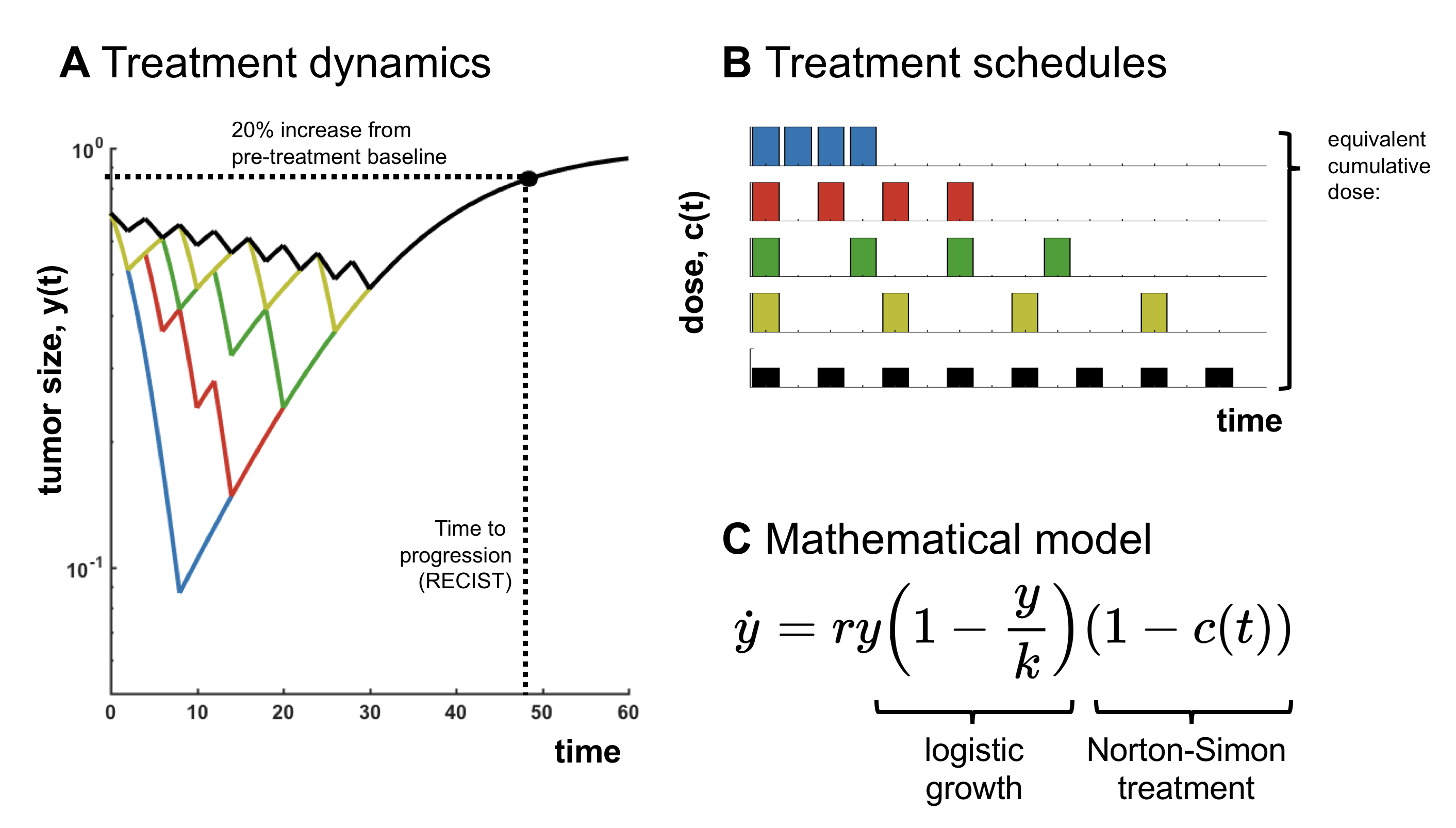

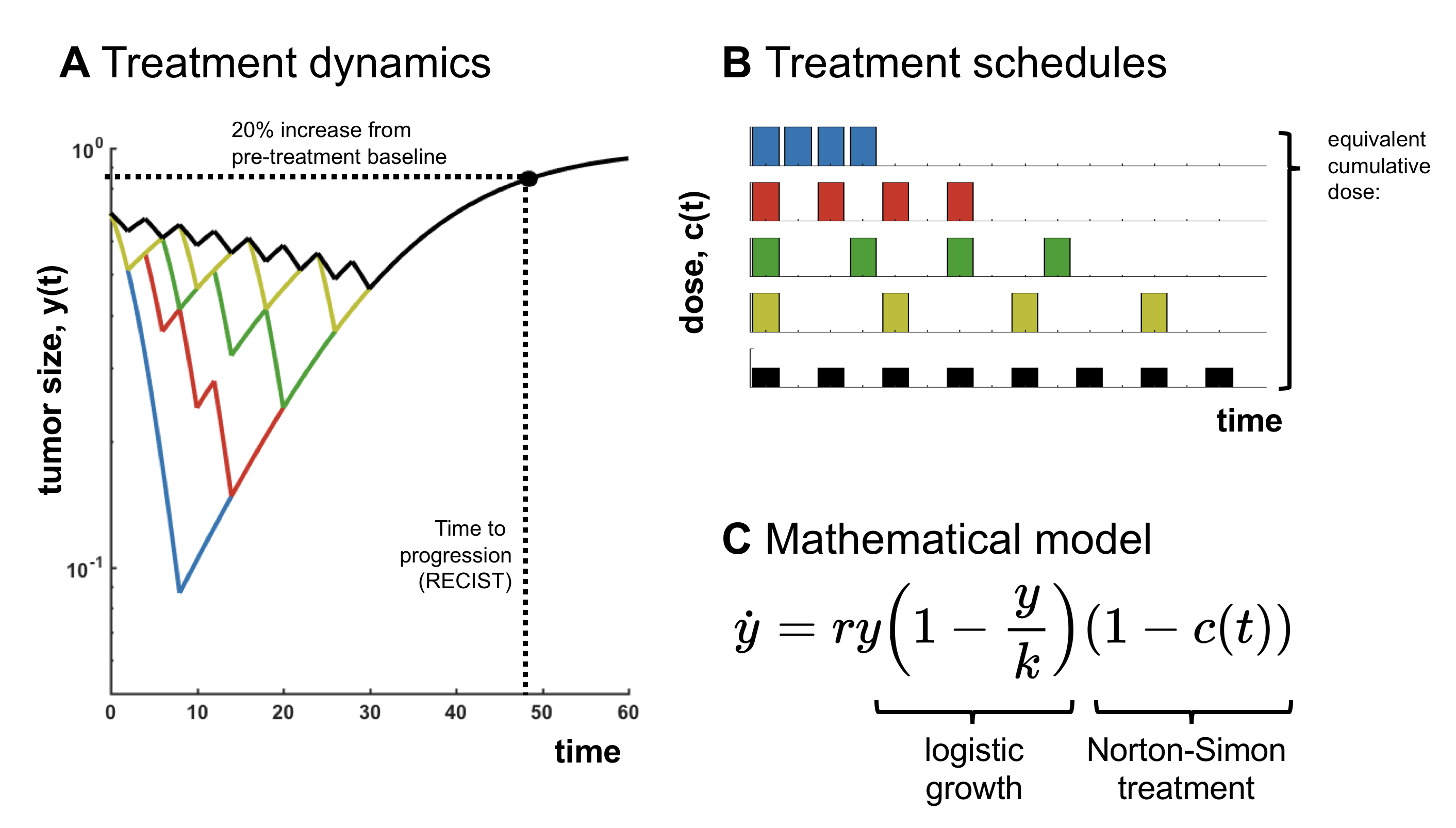

Here’s a historical result that many of us study as one of the first examples of math oncology: logistic growth with a "Norton-Simon" treatment. This models sigmoidal tumor growth (logistic) with tumor kill via chemotherapy with a kill rate proportional to the growth rate.

Simple simulation (or analysis) shows that if we consider treatment schedules which maintain an equivalent cumulative dose administered, the outcome (time to progression; TTP) is always identical. Of course, the

details depend on the tumor growth model and the treatment mechanism, but it raises an obvious question: does treatment personalization actually matter?

Our point of view is that treatment personalization is still extremely important. However, because the Norton-Simon model is so common, in many mathematical models the impact of schedule personalization is entangled with the effect of an altered cumulative dose. The purpose of this post is to raise awareness of this fact, introduce the concept of “first” and “second” order effects in treatment scheduling, and to explain their relevance in adaptive therapy.

The 1st and 2nd order effects of adaptive therapy

Adaptive cancer treatment in prostate cancer has two distinct differences from standard of care protocols. First, it consists of a

personalized dosing protocol dictating treatment "holidays" based on a patient-specific biomarker. Second, these treatment holidays result in a much lower

cumulative dose delivered over the course of the patient's treatment regimen (53% less).

Which is more important? Is it even possible to determine if scheduling is more important than total dose delivered?

We advocate for disentangling what we will call “first”- and “second”-order effects. First-order effects are those effects which are driven by the mean of dose delivered (cumulative dose), while second-order effects depend on the variance of dose delivered over time (the timing of treatment). Adaptive therapy alters both first- and second-order characteristics of a schedule (cumulative drug and timing). We must design math models to evaluate which is the most important.

Benefits of dose minimization (first-order effects)

The reason behind dose minimization in the adaptive trials is to leverage

competitive suppression between treatment sensitive and resistant subpopulations. This suppression is leveraged through proximity to carrying capacity - maintaining a large tumor volume - which is achieved by reducing cumulative dose.

But here's an interesting point: where the classical Norton-Simon model is employed as a representation of reality, it follows that progression is mostly driven by the cumulative dose, and scheduling has relatively little impact on TTP. In other words how we reduce the cumulative dose may not matter as much as the fact that we reduce it.

One (perhaps slightly controversial) corollary is that this may explain why some other intermittent trials in prostate cancer (and other cancer) have not demonstrated superiority. These trials often maintain the same cumulative dose in both arms, and have essentially demonstrated the “classical” Norton-Simon dynamics in action.

Benefits of dose personalization (second-order effects)

So, is personalized treatment adaptation

unnecessary? No. We believe that even if the above holds true, personalization of dosing still plays a key role. By adapting treatment breaks to patient-specific biomarkers, the protocol serves as a kind of "dose-finding" strategy to search for the patient-optimal minimized cumulative dose.

There are also practical caveats: an infinitesimal dose – even if given for many years - will clearly not be effective at delaying progression. So, there’s a limit to the extent to which this result holds, and adaptive treatment algorithms may be more robust than fixed schedules.

Re-connecting with the basics has been helpful in developing a deeper understanding of our current adaptive therapy models. In fact, quantifying the effect of schedule vs cumulative dose is an active line of research we are currently pursuing, under the terminology of "

antifragility." Math modeling has shown us that the strength of competition may play an important role in deciding the relative contribution of each. Watch this space for a pre-print.

Simple simulation (or analysis) shows that if we consider treatment schedules which maintain an equivalent cumulative dose administered, the outcome (time to progression; TTP) is always identical. Of course, the details depend on the tumor growth model and the treatment mechanism, but it raises an obvious question: does treatment personalization actually matter?

Our point of view is that treatment personalization is still extremely important. However, because the Norton-Simon model is so common, in many mathematical models the impact of schedule personalization is entangled with the effect of an altered cumulative dose. The purpose of this post is to raise awareness of this fact, introduce the concept of “first” and “second” order effects in treatment scheduling, and to explain their relevance in adaptive therapy.

Simple simulation (or analysis) shows that if we consider treatment schedules which maintain an equivalent cumulative dose administered, the outcome (time to progression; TTP) is always identical. Of course, the details depend on the tumor growth model and the treatment mechanism, but it raises an obvious question: does treatment personalization actually matter?

Our point of view is that treatment personalization is still extremely important. However, because the Norton-Simon model is so common, in many mathematical models the impact of schedule personalization is entangled with the effect of an altered cumulative dose. The purpose of this post is to raise awareness of this fact, introduce the concept of “first” and “second” order effects in treatment scheduling, and to explain their relevance in adaptive therapy.

Simple simulation (or analysis) shows that if we consider treatment schedules which maintain an equivalent cumulative dose administered, the outcome (time to progression; TTP) is always identical. Of course, the details depend on the tumor growth model and the treatment mechanism, but it raises an obvious question: does treatment personalization actually matter?

Our point of view is that treatment personalization is still extremely important. However, because the Norton-Simon model is so common, in many mathematical models the impact of schedule personalization is entangled with the effect of an altered cumulative dose. The purpose of this post is to raise awareness of this fact, introduce the concept of “first” and “second” order effects in treatment scheduling, and to explain their relevance in adaptive therapy.

Simple simulation (or analysis) shows that if we consider treatment schedules which maintain an equivalent cumulative dose administered, the outcome (time to progression; TTP) is always identical. Of course, the details depend on the tumor growth model and the treatment mechanism, but it raises an obvious question: does treatment personalization actually matter?

Our point of view is that treatment personalization is still extremely important. However, because the Norton-Simon model is so common, in many mathematical models the impact of schedule personalization is entangled with the effect of an altered cumulative dose. The purpose of this post is to raise awareness of this fact, introduce the concept of “first” and “second” order effects in treatment scheduling, and to explain their relevance in adaptive therapy.